*tote bag in production

Communities of color have been and are over policed in the United States, whether through the criminalization of the previously enslaved with loitering laws or the ‘War on Drugs’ more recently. Thus, voting rights for the previously incarcerated play a large role in civil rights and representation.

While federal laws like the Voting Rights Act of 1965 offer a baseline for voting rights across the country, it is ultimately up to the states to decide what elections looks like for their residents.

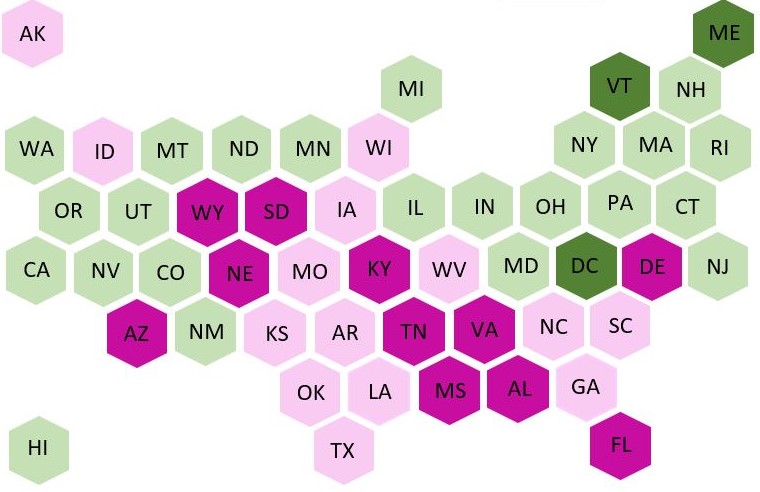

To highlight this, the tote bag map was chosen to showcase how different suffrage can be depending on where one lives in the United States. This is especially relevant in terms of voting rights for the formerly incarcerated, which range from always retaining one’s right to vote to permanent disenfranchisement.

understanding the tote bag

The tote bag displays the varying levels of voting rights for the formerly incarcerated in the U.S. with each colorful hexagon representing a state. The data for this is from the Movement Advancement Project, which tracks a variety of democracy as well as LGBTQIA+ related legislation by state.

Voting rights for the formerly incarcerated are represented as such:

- Dark Green: never loses voting rights

- Light Green: regains voting rights once out of prison

- Light Pink: regains voting rights after entire sentence (including parole and/or probation) is served

- Dark Pink: additional steps are required to regain voting rights once sentence is served

- For example: paying off court debts

Ties to Civil Rights

Voting is one of the most important ways citizens can affect change in the United States. In addition to no longer being able to serve on a jury or run for state office, convicted felons may also permanently lose their right to vote depending on what state they reside in.

With over 4.6 million citizens unable to vote in 2022 in the United States, felony disenfranchisement greatly impact civil rights.

“Indeed, the felony disfranchisement rate in the United States has grown by 500 percent since 1980”

Anderson, 93

In addition to varying levels of voting rights by state, the type of crime that disenfranchises varies as well. Much like the vagrancy laws of the black codes and Jim Crow era, which were used to criminalize the formerly enslaved, many states write that crimes of ‘moral turpitude’ result in the loss of the right to vote.

This vague phrase ensures that enforcement is different in each state. For example, in Alabama, a crime of moral turpitude includes murder, endangering the water supply, and forgery.

Given the United States’ history of mass incarceration and racial inequities in sentencing, convictions, and arrests, this issue blatantly impacts communities of color.

Representation

“Under the three-fifths compromise, 60 percent of African Americans were counted toward apportionment. Under Florida’s felon disenfranchisement laws, only 60 percent of its African American citizens had the right to vote — different century, same result.”

Daniels, 170

Population count is another issue with felony disenfranchisement. Much like the three-fifths compromise, where the enslaved were only counted as three-fifths of a person when determining the population of a state (and how many representatives it would get in congress), the U.S. census counts those incarcerated as part of a state’s population.

As a result, a state may receive more representatives in congress or congressional districts may be drawn based on prison populations — despite many citizens losing their right to vote when in prison or after serving their sentence.

Regaining the right to vote

Similar to poll taxes, which required those trying to vote to pay a yearly fee, a practice that was made illegal federally in 1964 with the 24th Amendment, the previously incarcerated in Virginia, Kentucky, and Mississippi are required to pay fees or court fines to regain their right to vote.

Given that the formerly incarcerated face difficulties finding jobs and are often lower income before their incarceration, this qualification makes it so only those with financial resources are able to regain their right to vote.

Conclusion

The United States’ history of racial discrimination in its criminal justice system impacts the felony disenfranchisement we see today.

With different and changing laws in each state, many formerly incarcerated citizens are afraid to cast their ballot or are unaware that their right to vote has been restored. Additionally, in 2022, “three out of four people disenfranchised are living in their communities, having fully completed their sentences or remaining supervised while on probation or parole.”

As a result, this issue has implications on recidivism and racial and social justice in the country.

Take Action today to learn more about this issue and how people are fighting to reform the criminal justice system in the United States.

Work Cited

Movement Advancement Project. “Voting Rights for Formerly Incarcerated People.” https://www.mapresearch.org/democracy-maps/voting_rights_for_formerly_incarcerated_people. Accessed 05/03/2023.

Anderson, Carol. One Person, No Vote: How Voter Suppression Is Destroying Our Democracy.

Daniels, Gilda. “Felon Disenfranchisement.” Uncounted: The Crisis of Voter Suppression in America. New York University Press. NY. 2020